Open World Games and the Myth of Sisyphus

To the memory of Kevin Conroy. There was only ever one true Batman.

You have been playing for months. Slowly and steadily, you have harvested every collectable - making yourself stronger and stronger until you can kill the toughest enemies. Every enemy defeated, every monster slain. No side quest worth doing remains. Those not worth doing are also done because you are a completionist (which is a dignified way of saying that you have no life). No part of the open world remains unexplored - you have climbed the tallest mountain and dived the deepest sea. All of this, you have done on the highest difficulty level. All the DLC is exhausted, too. The strongest creature in the world is you.

What do you do now?

And when Alexander saw the breadth of his domain, he wept, for there were no more worlds to conquer.

This post is woven out of several journal entries I wrote about games I have played and some of the most important books I have read recently. This is not a thesis or a contention - it is simply an exploration of loosely, tenuously connected themes I found in games and books.

“One does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write a manual of happiness.”1

- Albert Camus

I never really knew what people mean by grinding in video games. When I did hear the word, I certainly did not appreciate its negative connotations. My brother used to grumble about how collecting Riddler trophies became a “chore” (it is one of the most hated things among otherwise fanatic Batman: Arkham players). I would dismiss the grumbling thinking that collecting those trophies was simply an optional part of the game - you did not have to do it. In the Arkham games, side missions have no consequence apart from the XP boosts. They do not add to or take away anything from the gameplay experience.

Then, Arkham Knight came along. As I neared the end of the game, I realized that I could not sustain my attitude towards Riddler trophies. Arkham Knight rewards you for being a completionist - complete the whole game and you are rewarded with a breathtaking cutscene (I won’t spoil it here, but search for “the Knightfall Protocol” on YouTube). Unfortunately, reaching a 100% meant collecting all of the Riddler trophies - all 243 of them - which is maddening. Now I knew what my brother meant.

And even going around collecting the trophies is not grinding in the true sense of the word. A grinding process in a well-designed crafting system not only inches you towards the 100% completion, but also makes your character better and stronger (Arkham games don’t have a very sophisticated crafting system or build tree). It wasn’t until I played Fallout 4 that I really understood this. In Fallout 4, I’ve spent hours scouring the wasteland on foot, scavenging for rare materials (like lead or adhesive) so I could use them to build better radiation-resistant armour or weapons to kill special enemies. Even though I spent more time scavenging in Fallout 4 than collecting Riddler trophies in Arkham Knight - the former felt a lot more rewarding, because it was building up to something more than just a cutscene (albeit a spectacular one).

The hours spent wandering the wasteland in Fallout 4 quickly became days and weeks and months. And then, in early 2020, I acquired the mother of all open world games - The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. This was just before the pandemic, and the lockdown meant that I’d have a lot more time to play games. What was months for Fallout 4 became years for the Witcher. I’m playing the game to this day, and I’m not done. I still have more character builds to try, difficulty levels to beat, potions to brew and in-game choice trees to explore (there are nearly 40 different ways to end that game).

I have no reasonable answer for why I’m still playing that game 3 years later. The YouTube channel Gameological Dig makes an excellent attempt to explain what made the Witcher 3 revolutionary. The sophisticated crafting system, the poignant writing, pacing and the stellar voice acting all contribute to the appeal of the game. As the video states, every interaction with side characters is heavy with personal history and emotion. This makes it easy to justify side quests. In addition to these, there are plenty of design principles which the developers have employed which make the game more addictive. Moreover, it is a game based on a well known series of fantasy books - so the game world is already full of myth and lore (something that is absent in Fallout). The open world itself is very detailed (CD Project Red invented the 30 second rule to keep the world engaging. The YouTuber Luke Stephens has a fantastic series of videos where he has applied this rule to various games, including the Witcher 3, to see how it affects the game). Finally, the combat isn’t all hacking and slashing - you have to pause and think hard before engaging an enemy (it takes preparation within the game too).

And yet, none of this saves me from the bleak moment that comes at the end of the game. In that moment, I am Sisyphus, watching the rock roll hopelessly to the bottom of the mountain.

Yes, I do look forward to the next playthrough - this time, perhaps on a higher difficulty level, or with a different set of weapons. “I’ll have to build my character all over gain, that will take weeks…”, I think with a groan. But I still do it. All to check off an arbitrary item on an invisible to-do list. And if I do manage to finish this invisible to-do list, there will be another one for another game. And I’ll keep pushing that boulder up the hill over and over again.

One must imagine Sisyphus happy

Open world games are absurd and thoroughly meaningless. But then, so is life. Like in the games, the moral or economic worth of whatever we seek in life is determined by a wholly arbitrary value system. Just how arbitrary these value systems are is a discussion which would exhaust all conscious thought in the universe, if we let it. What matters is that they are arbitrary. If they were not, there would be no room for more than one religion or ideology. Only a Descartes would have the courage to question whether an ideology has been merely dreamt up, or if it is the result of critical scrutiny. The rest of us do not have the time to subject everything, everyday to scepticism.

And thus, the void left behind by the absence of critical judgement starts getting filled with Sisyphean systems - just like in the games. We dream up minimaps, side-quests and collectathons in life, just like in the games. These dreamt up objectives seem meaningful to us only because other people believe them to be meaningful. They are worth whatever we, as a civilization, decide they are worth.

But the world is indifferent to it. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes,

“The foremost reason happiness is so hard to achieve is that the universe was not designed with the comfort of human beings in mind… natural processes do not take human desires into account.”2

It is natural that Csikszentmihalyi, as the foremost expert on enjoyment, begins his book with a chapter titled “Happiness Revisited”. But it is just as unsurprising that the focal point of this chapter is a section titled “The Roots of Discontent” (I refer to Csikszentmihalyi and his book several times in this article. It is a matter of some pride to me that by the time I am drafting this, I can finally pronounce and spell his last name without assistance.) He echoes Camus’ suggestion of a happy Sisyphus,

… there is no inherent problem in our desire to escalate our goals, as long as we enjoy the struggle along the way. The problem arises when people are so fixated on what they want to achieve that they cease to derive pleasure from the present. When that happens, they forfeit their chance of contentment.3

Just as your life is indifferent to what your character does within a game (unless you’re a professional gamer), the universe is also indifferent to whatever invisible checklist you write for yourself. This is not difficult to see. But once seen, it cannot be unseen. Trying to reconcile the indifferent universe with human endeavour (or failing to doing so) is at the very root of existential thought. Becoming conscious of the pointlessness of this uphill task has inspired centuries of lament. The very awareness of this problem is the real problem. It is no accident that the greatest soliloquy written in the English language is “To be, or not to be, that is the question…”4. It ends with a conclusion that seems all too inevitable - “conscience makes cowards of us all”.

This realisation is crippling. If nothing matters, why bother doing anything at all? This paralyzing thought echoes throughout history. It was there long before Shakespeare or Camus. And it will be there, as long as there is a place in the universe where conscious thought exists. It is central to the human condition. Dostoevsky wrote, in Notes from the Underground,

… the direct, immediate, legitimate fruit of heightened consciousness is inertia, that is, the deliberate refusal to do anything… all spontaneous people, men of action, are active because they are stupid and limited.5

The Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib (who was both a notorious cynic and a hopeless romantic - I see no contradiction), wrote along similar lines

The prison of life and bonds of sorrow are one and the same. Why, then, should one be free of suffering whilst they live?

Why despair, O Ghalib! The world will go on, even without you.6

The inevitability of this despair is thus established. After the despair comes acceptance. And it is only from this acceptance that hope can sprout. Camus, in his essays on absurdism acknowledges that the most important question in life is whether it is worth living. He ruthlessly simplifies the problem by introducing a proxy - “There is but one serious philosophical problem and that is suicide.”7 This brutal simplification is necessary, it strips off the convenience of misinterpretation. He argues further that it is only when confronted with this stark realization, that we can truly begin to fix the problem.

Sisyphus… knows the whole extent of his wretched condition; it is what he thinks of during this descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.8

We need not even arrive at this acceptance from a metaphysical perspective, like Camus did. The journalist Oliver Burkeman suggests that not only is acceptance of the absurd eminently practical, it may even be therapeutic!

The day will never arrive when you finally have everything under control - when the flood of emails has been contained; when your to-do lists have stopped getting longer; when you’re meeting all your obligations at work and in your home life; when nobody’s angry with you for missing a deadline or dropping the ball; and when the fully optimized person you’ve become can turn, at long last, to the things life is really supposed to be about. Let’s start by admitting defeat: none of this is ever going to happen.

But you know what? That’s excellent news.9

(Emphasis in original)

This is how Burkeman concludes the introduction to his book Four Thousand Weeks - Time Management for Morals. The remainder of the book is a refreshing, subversive take on productivity - exhorting readers to instead embrace their finitude, and appreciate what they really can exercise control over. Csikszentmihalyi lays the foundations of the flow experience in very much the same terms.

Finding Flow - Getting Sisyphus to Enjoy Himself

My wife takes a brief summer vacation every year. This is when I usually catch up on my gaming. I pour myself a beer, make some popcorn (although it is more for my dog’s benefit - nothing makes her sit quietly by my side like the smell of popcorn). I also use this time to catch up on my other hobbies and side-projects. This year, my wife’s travels ended up lasting three weeks. I spent all that time playing God of War (2018) and reading Csikszentmihalyi. In any other year, I would have just replayed Arkham Knight, Fallout 4 or The Witcher. But this year, one of the most anticipated entries in the God of War franchise, God of War: Ragnarök was going to come out in November. I’d had it’s prequel lying around for ages which I’d never started playing. So I started playing it - mostly as homework for Ragnarök.

I just couldn’t stop playing it!

I’m currently in my first NG+ playthrough. Like other games, its the side quests that make it addictive. I absolutely loved hunting down the Valkyries and painstakingly learning how to defeat them. When I played the game a second time, I got to them as quickly as possible. God of War takes place across the multiple realms of Norse myth, of which two realms - Muspelheim (the fire realm) and Niflheim (the fog realm) - are optional; you can finish the game without setting foot in them. The first time I played the game, I went through the rigmarole of playing through them simply because I didn’t know better, and I needed the loot there for upgrading weapons and armour. Once I was done with them, I would never go back. But during my second playthrough, I realized that I kept going back to both Muspelheim and Niflheim every time I was bored with the main storyline (which takes place in the default realm - Midgard).

This was remarkable. What seemed a punishment once had become something I looked forward to. I realized that after a very long time, I was actually enjoying the experience more than the rewards!

How do these side quests go from annoying distractions to becoming the central purpose of the game? How do you get a player to ignore the central storyline? I imagine that like me, most gamers, are in it for the story and the campaign. What do designers do that brings about such a significant change in the players' attitude? Side quests are the most ridiculous things to be addicted to. But I can’t describe in words the sense of satisfaction I’d get when Kratos successfully beats a Valkyrie and rips her wings off (but not before she literally wipes the floor with him many times over). I’ve never felt that kind of satisfaction in any other game.

It’s because of the loop that the game has instilled in my mind. The loop has a sense of familiarity that would take me weeks to build in any other game (perhaps with the exception of the Arkham games - renowned for their revolutionary combat system). Try hitting, get hit, learn how to hit well, learn how to not get hit, learn enemy moves, get better weapons, defeat harder enemies, earn rewards, ad inifitum10. Keep doing this until there’s a sense of accomplishment.

Sure, this sense of achievement is based on a wholly arbitrary checkpoint - but that does not bother me anymore. The game, thus, has done something remarkable. It has made me addicted, but not in a mindless way. It definitely takes skill, patience and practice to do well. I’d go so far as to say that it takes study. It has converted something Sisyphean into something heavily, obsessively sought. I’d need coffee before beginning to code, but I could probably be sleep deprived and still play God of War for hours and hours. How does a game accomplish all of this? Perhaps the answer lies in what Csikszentmihalyi calls the conditions of Flow.

While Csikszentmihalyi devotes an entire chapter to the conditions conducive to flow, I think the single most important condition is,

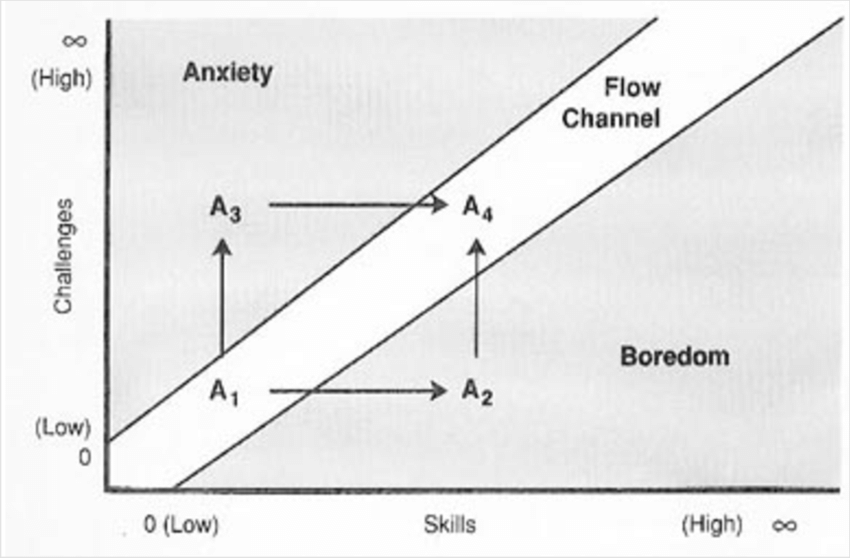

… enjoyment comes at a very specific point: whenever the opportunities for action (challenges) perceived by the individual are equal to his or her capabilities11

The chart above highlights a “flow channel” - the region where the player’s skills and the challenges they face are commensurate. If a non-skilled player faces a difficult challenge, they become anxious. If a skilled player faces an easy task, they get bored.

Video games have solved this problem. Most modern games begin with tutorials disguised as stories - players usually don’t even realize that they’re being taught. Enemy upscaling is an absolute life-saver in The Witcher (eventually Geralt becomes so powerful that defeating enemies becomes boring - unless the player decides to turn on the enemy upscaling feature). In God of War, the Valkyries are easily the toughest bosses - who are usually located in isolated areas known as “Odin’s Hidden Chambers”. The game does not let you simply walk into one of these - essentially ensuring that you have done your homework. Thus, video game design has grown to navigate the flow channel remarkably well, by employing various mechanics such as in-game tutorials, scaling enemies, and ensuring that the players don’t end up in dangerous situations prematurely.

Csikszentmihalyi, too, emphasizes design heavily. When mentioning activities that his respondents described as “flow inducing”, he further deconstructs the conditions of flow as follows:

What makes these activities conducive to flow is that they were designed to make optimal experience easier to achieve. They have rules that require the learning of skills, they set up goals, they provide feedback, and they make control possible12.

(Emphasis in original)

The lead gameplay designer on God of War, Jason McDonald, mirrors these ideas in his talk about reinventing God of War’s gameplay.

In summary, it seems that achieving flow is a matter of good design. So, if Sisyphus’ environment - the rock and the mountain included - was designed well enough, could we get him to enjoy himself? Further, his life and his universe, unlike ours, is not chaotic. On the one hand we have a Sisyphean rut, and on the other, the ineffable chaos of daily life. These are two extremes of a spectrum. Do all our activities sit on this spectrum?

It is certainly tempting to think so. The closer something is to the Sisyphean end, the better suited it is for gamification. On the other hand, something that is closer to the chaotic end is, to begin with, not boring. But that alone does not make it fun. We still have to seek some order in the chaos.

We are thus left with a precarious tradeoff. But as it turns out, there is little merit in actually solving it - even if you had the godlike ability to do so.

The Future is Today - Ragnarök is Now

There seems to be deep-seated cultural, perhaps even religious, motivation for solving this tradeoff. Almost all religious cosmologies in the west are linear. We’re all headed somewhere, hopefully to a peaceful void. As Charles Dickens wrote in A Christmas Carol, we’re all fellow passengers to the grave. The abstract future thus becomes some fixed point in time; even if, paradoxically, we have no idea how far we are from it. It is natural, then, that we want to pull our lives away from the chaos and towards order - hopefully well before Armageddon.

Eschatology in the east, however, is either cyclic (like in Hinduism or Buddhism) or simply absent (like in the Tao or Shinto). Future never comes because everywhen is simultaneously the past and the future of sometime else. (The only western myth that has a cyclic religious cosmology is Norse. It is in this mythology that the latest God of War games are set - what a delicious coincidence!)

In the same spirit, Burkeman makes an argument that the future will never arrive - at least not the future we plan for.

… you can’t depend on fulfilment arriving at some distant point in the future, once you’ve got your life in order, or met the world’s critera for success.13

This supposedly ideal future is problematic because there is no progress bar to tell us how close we are (one of the universally hated things in gaming, too, is an invisible progress bar). Sure, we replace the progress bar with checkpoints - finishing college, getting a job, doing great work, having great relationships, retiring, dying.

But, look around yourself - I bet the happiest and most interesting people you know have little respect for progress bars or checkpoints. They might have finished college but they are constantly learning. Getting a good job isn’t a checkpoint for them - they’ve transcended that. They thrive on challenges, and they certainly don’t intend to retire. These are people who possess, as Csikszentmihalyi calls it, an autotelic self14. They identify challenges and set goals. They are capable of getting fully immersed in activity - with sustained, active attention. And above all, they’ve learned to enjoy immediate experience. In other words, they’ve transcended existential dread.

Call one of them right now.

It’s the end of 2022. Gaming consoles aren’t getting any cheaper since the global chip shortage, but I’m finally going to play God of War: Ragnarök before the year ends.

It is only from the debris of Ragnarök that hope can sprout. And I have exactly the right book to help me with making the most of the debris: Tim Harford’s Messy: How to be Resilient in a Tidy-minded World.

Watch this space for more essays on books and games.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Aaditya Bugga and Dr Charusmita for reviewing early drafts of this post.

-

[P88] Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Penguin Modern Classics, 2013. ↩︎

-

[P8] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Rider Books, 2002. ↩︎

-

Csikszentmihalyi, P10 ↩︎

-

Shakespeare. Hamlet. Act 3, Scene 1. ↩︎

-

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Notes from the Underground. Project Gutenberg eBook edition. Part I, Chapter V. ↩︎

-

The Urdu version, romanized, can be found on rekhta.org ↩︎

-

Camus, P5 ↩︎

-

Camus, P87-88 ↩︎

-

[P14] Burkeman, Oliver. Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. Penguin Vintage, 2022 ↩︎

-

Combat in video games must be a lot more than just button-mashing. Funnily, if you do too much of that in the Arkham games, the Riddler taunts Batman: ‘You’re a cheat and a liar. A dressed-up strongman playing with expensive toys. “World’s greatest detective?” Hah! And everyone from Gotham to Star City believes it!’ ↩︎

-

Csikszentmihalyi, P52 ↩︎

-

Csikszentmihalyi, P72 ↩︎

-

Burkeman, P204 ↩︎

-

Csikszentmihalyi, P208 ↩︎